Famous Freemasons - Edward Jenner

EDWARD ANTHONY JENNER (1749-1823)

Food For Thought

VACCINATION

In 1757, an 8-year-old boy was inoculated with smallpox in Gloucester; he was one of thousands of children inoculated that year in England. The procedure was effective, as the boy as he developed a mild case of smallpox and was subsequently immune to the disease. His name was Edward Jenner.

Edward Anthony Jenner was born on 17 May 1749 in Berkeley, Gloucestershire. He was the eighth of nine children, who all received a good education. His father, the Reverend Stephen Jenner was the vicar of Berkeley. He went to school in Wotton-under-Edge and Cirencester.

His inoculation for smallpox had a lifelong effect upon his general health. In 1764, Jenner began his apprenticeship with George Harwicke. During these years, he acquired a sound knowledge of surgical and medical practice. Upon completion of this apprenticeship at the age of 21, Jenner went to London and became a student of John Hunter, who was on the staff of St. George's Hospital in London. Hunter was not only one of the most famous surgeons in England, but he was also a well-respected biologist, anatomist, and experimental scientist. The firm friendship that grew between Hunter and Jenner lasted until Hunter's death in 1793. Although Jenner already had a great interest in natural science, the experience during the 2 years with Hunter only increased his activities and curiosity. Jenner was so interested in natural science that he helped classify many species that Captain Cook brought back from his first voyage. In 1772, however, Jenner declined Cook's invitation to take part in the second voyage.

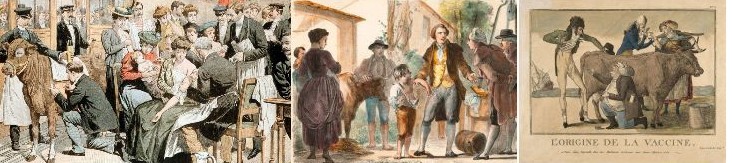

3 Portaits of Edward Jenner, and a painting of the first vaccination

Jenner occupied himself with many matters. He studied geology and carried out experiments on human blood. In 1784, after public demonstrations of hot air and hydrogen balloons by Joseph M. Montgolfier in France during the preceding year, Jenner built and twice launched his own hydrogen balloon. It flew 12 miles.

Following Hunter's suggestions, Jenner conducted a study of the life of the nested cuckoo. The final version of Jenner's paper was published in 1788 and included the original observation that it is the cuckoo hatchling that evicts the eggs and chicks of the foster parents from the nest. Jenner also demonstrated a specific anatomical adaptation in the cuckoo hatchling.

"The singularity of its shape is well adapted to these purposes; for, different from other newly hatched birds, its back from the scapula downwards is very broad, with a considerable depression in the middle. This depression seems formed by nature for the design of giving a more secure lodgement to the egg of the Hedge-sparrow, or its young one, when the young Cuckoo is employed in removing either of them from the nest. When it is about twelve days old, this cavity is quite filled up, and then the back assumes the shape of nestling birds in general."

In addition he noted that the adult does not remain long enough in the area to perform this task.

For this remarkable work, Jenner was elected a fellow of the Royal Society. However, many naturalists in England dismissed his work as pure nonsense. For more than a century, antivaccinationists used the supposed defects of the cuckoo study to cast doubt on Jenner's other work. Jenner was finally vindicated in 1921 when photography confirmed his observation. At any rate, there is no doubt that Jenner had a lifelong interest in natural sciences. His last work, published posthumously, was on the migration of birds.

Following Hunter's suggestions, Jenner conducted a study of the life of the nested cuckoo. The final version of Jenner's paper was published in 1788 and included the original observation that it is the cuckoo hatchling that evicts the eggs and chicks of the foster parents from the nest. Jenner also demonstrated a specific anatomical adaptation in the cuckoo hatchling.

"The singularity of its shape is well adapted to these purposes; for, different from other newly hatched birds, its back from the scapula downwards is very broad, with a considerable depression in the middle. This depression seems formed by nature for the design of giving a more secure lodgement to the egg of the Hedge-sparrow, or its young one, when the young Cuckoo is employed in removing either of them from the nest. When it is about twelve days old, this cavity is quite filled up, and then the back assumes the shape of nestling birds in general."

In addition he noted that the adult does not remain long enough in the area to perform this task.

For this remarkable work, Jenner was elected a fellow of the Royal Society. However, many naturalists in England dismissed his work as pure nonsense. For more than a century, antivaccinationists used the supposed defects of the cuckoo study to cast doubt on Jenner's other work. Jenner was finally vindicated in 1921 when photography confirmed his observation. At any rate, there is no doubt that Jenner had a lifelong interest in natural sciences. His last work, published posthumously, was on the migration of birds.

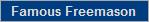

Contemporary cartoons against Jenner with an anti-vaccination themes

In addition to his training and experience in biology, Jenner made great progress in clinical surgery while studying with John Hunter in London. Jenner devised an improved method for preparing a medicine known as tartar emetic (potassium antimony tartrate). In 1773, at the end of 2 years with John Hunter, Jenner returned to Berkeley to practice medicine. There he enjoyed substantial success, for he was capable, skillful, and popular. Jenner was a founder of the Fleece Medical Society or Gloucestershire Medical Society, so called because it met in the Fleece Inn, Rodborough. It was a supper club meeting to dine together and read papers on medical subjects. He contributed papers on angina pectoris, ophthalmia, and cardiac valvular disease and commented on cowpox. He also belonged to a similar society which met in Alveston, near Bristol. He played the violin in a musical club and wrote light verse and poetry. As a natural scientist, he continued to make many observations on birds and the hibernation of hedgehogs and collected many specimens for John Hunter in London.

Jenner became a Freemason, was raised to the sublime degree of master mason 30 December 1802, in Lodge of Faith and Friendship No. 449. From 1812 to 1813 he was worshipful master of Royal Berkeley Lodge of Faith and Friendship.

In March 1788 Jenner married Catherine Kingscote and it is speculated that he might have met her while he and other fellows were experimenting with balloons. Jenner's trial balloon descended into Kingscote Park, Gloucestershire, owned by Anthony Kingscote, one of whose daughters was Catherine.

He earned his MD from the University of St Andrews in 1792. He is credited with advancing the understanding of angina pectoris. He once wrote, "How much the heart must suffer from the coronary arteries not being able to perform their functions."

While Jenner's interest in the protective effects of cowpox began during his apprenticeship with George Harwicke, it was 1796 before he made the first step in the long process whereby smallpox, the scourge of mankind, would be totally eradicated. For many years, he had heard the tales that dairymaids were protected from smallpox naturally after having suffered from cowpox. Pondering this, Jenner concluded that cowpox not only protected against smallpox but also could be transmitted from one person to another as a deliberate mechanism of protection.

Jenner became a Freemason, was raised to the sublime degree of master mason 30 December 1802, in Lodge of Faith and Friendship No. 449. From 1812 to 1813 he was worshipful master of Royal Berkeley Lodge of Faith and Friendship.

In March 1788 Jenner married Catherine Kingscote and it is speculated that he might have met her while he and other fellows were experimenting with balloons. Jenner's trial balloon descended into Kingscote Park, Gloucestershire, owned by Anthony Kingscote, one of whose daughters was Catherine.

He earned his MD from the University of St Andrews in 1792. He is credited with advancing the understanding of angina pectoris. He once wrote, "How much the heart must suffer from the coronary arteries not being able to perform their functions."

While Jenner's interest in the protective effects of cowpox began during his apprenticeship with George Harwicke, it was 1796 before he made the first step in the long process whereby smallpox, the scourge of mankind, would be totally eradicated. For many years, he had heard the tales that dairymaids were protected from smallpox naturally after having suffered from cowpox. Pondering this, Jenner concluded that cowpox not only protected against smallpox but also could be transmitted from one person to another as a deliberate mechanism of protection.

The hand of Sarah Nelms with cowpox, 3 examples of small pox (the lucky ones) with one uninfected child as comparison

In May 1796, Edward Jenner found a young dairymaid, Sarah Nelms, who had fresh cowpox lesions on her hands and arms. On May 14, 1796, using matter from Nelms' lesions, he inoculated an 8-year-old boy, James Phipps. Subsequently, the boy developed mild fever and discomfort in the axillae. Nine days after the procedure he felt cold and had lost his appetite, but on the next day he was much better. In July 1796, Jenner inoculated the boy again, this time with matter from a fresh smallpox lesion. No disease developed, and Jenner concluded that protection was complete.

In 1797, Jenner sent a short communication to the Royal Society describing his experiment and observations. However, the paper was rejected. Then in 1798, having added a few more cases to his initial experiment, Jenner privately published a small booklet entitled An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae, a disease discovered in some of the western counties of England, particularly Gloucestershire and Known by the Name of Cow Pox. The Latin word for cow is vacca, and cowpox is vaccinia; Jenner decided to call this new procedure vaccination. The 1798 publication had three parts. In the first part Jenner presented his view regarding the origin of cowpox as a disease of horses transmitted to cows. The theory was discredited during Jenner's lifetime. He then presented the hypothesis that infection with cowpox protects against subsequent infection with smallpox. The second part contained the critical observations relevant to testing the hypothesis. The third part was a lengthy discussion, in part polemical, of the findings and a variety of issues related to smallpox. The publication of the Inquiry was met with a mixed reaction in the medical community.

Jenner went to London in search of volunteers for vaccination. However, after 3 months he had found none. In London, vaccination became popular through the activities of others, particularly the surgeon Henry Cline, to whom Jenner had given some of the inoculant. Later in 1799, Drs. George Pearson and William Woodville began to support vaccination among their patients. Jenner conducted a nationwide survey in search of proof of resistance to smallpox or to variolation among persons who had cowpox. The results of this survey confirmed his theory. Despite errors, many controversies, and chicanery, the use of vaccination spread rapidly in England, and by the year 1800, it had also reached most European countries.

Although he received worldwide recognition and many honors, Jenner made no attempt to enrich himself through his discovery. Jenner's continuing work on vaccination prevented him from continuing his ordinary medical practice. He was supported by his colleagues and the King in petitioning Parliament, and was granted £10,000 in 1802 for his work on vaccination. In 1807, after the Royal College of Physicians had confirmed the widespread efficacy of vaccination. the Parliament awarded him £20,000 more. However, he not only received honors but also found himself subjected to attacks and ridicule. Despite all this, he continued his activities on behalf of the vaccination program. Gradually, vaccination replaced variolation, which became prohibited in England in 1840.

In 1803 in London, he became president of the Jennerian Society, concerned with promoting vaccination to eradicate smallpox. The Jennerian ceased operations in 1809. In 1808, with government aid, the National Vaccine Establishment was founded, but Jenner felt dishonoured by the men selected to run it and resigned his directorship. Jenner became a member of the Medical and Chirurgical Society on its founding in 1805 and presented a number of papers there. The society is now the Royal Society of Medicine. He was elected a foreign honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1802. In 1806, Jenner was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Returning to London in 1811, Jenner observed a significant number of cases of smallpox after vaccination. He found that in these cases the severity of the illness was notably diminished by previous vaccination. In 1821, he was appointed physician extraordinary to King George IV, a great national honour, and was also made mayor of Berkeley and justice of the peace. He continued to investigate natural history, and in 1823, the last year of his life, he presented his "Observations on the Migration of Birds" to the Royal Society.

Jenner had married in 1788 and fathered four children. The family lived in the Chantry House, which became the Jenner Museum in 1985. Jenner built a one-room hut in the garden, which he called the “Temple of Vaccinia”, where he vaccinated the poor for free. After a decade of being honored and reviled in more or less equal measure, he gradually withdrew from public life and returned to the practice of country medicine in Berkeley. In 1810, his oldest son, Edward, died of tuberculosis. His sister Mary died the same year and his sister Anne 2 years later. In 1815, his wife, Catherine, died of tuberculosis. Sorrows crowded in on him, and he withdrew even further from public life. In 1820, Jenner had a stroke from which he recovered. On January 23, 1823, he visited his last patient, a dying friend. The next morning Jenner failed to appear for breakfast; later that day he was found in his study. He had had a massive stroke. Edward Jenner died during the early morning hours of Sunday, January 26, 1823. He was laid to rest with his parents, his wife, and his son near the altar of the Berkeley church.

Therefore Edward Jenner is credited with inventing vaccination, but in modern times some have discredited him for deliberately infecting his guinea pig with smallpox to see if he was immune. Many people have considered this to be unethical and un-masonic, but a closer look clears this misconception.

The following article by Andrew George entitled “Would Jenner's smallpox experiment pass a research ethics committee?” answers that very question

WOULD JENNER'S SMALLPOX EXPERIMENT PASS A RESEARCH ETHICS COMMITTEE?

The case seems indisputable. On May 14, 1796 Jenner vaccinated James Phipps, the eight-year-old son of his gardener, with material obtained from a milkmaid who had cowpox. A few weeks later he deliberately infected Phipps with smallpox to see if he would develop the disease. What could be more unethical than exposing a young boy to one of the most deadly diseases in the world simply to see if an unknown procedure would work?

But the story is more complex than this simple narrative suggests. In the 18th century, doctors carried out a procedure known as variolation to protect people from smallpox. This involved exposing people to a small dose of smallpox in order to give them a mild form of the disease, thereby protecting them from the full effects of the disease. It was not a risk-free procedure, and people often died as a result. However, given the terrible mortality of smallpox this was seen to be worthwhile.

Variolation had a long history in China, the Middle East and Africa. Its history in Britain was started by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, one of the most colourful characters in immunology. She originally eloped with her husband, and then went with him to Constantinople where he was ambassador.

Wortley Montagu wrote extensively about Ottoman life, wore Turkish dress, visited harems and Turkish baths and disguised herself as a man in order to get into the Hagia Sophia mosque. While in Constantinople, she came across the practice of variolation and, in 1718, had her young son Edward variolated on the wrist with a 'blunt and rusty needle'.

Returning to England she resumed life in society. She was a friend of the poet, Alexander Pope, who admired her intelligence and wit and was probably in love with her. In 1721 a smallpox epidemic was threatening Britain, and she persuaded Charles Maitland, her doctor in Constantinople, to variolate her daughter.

Wortley Montagu was a friend of Caroline, the Princess of Wales, who was also worried about the safety of her children. It's thought that this was what prompted the interest of Britain's royal family in variolation.

Sir Hans Sloane (later founder of the British Museum) organised 'The Royal Experiment' in 1721, in which six condemned prisoners from Newgate Prison were variolated. They were then pardoned and released.

You might question several aspects of the ethics of this experiment. To see if this protected them from smallpox, Sloane paid for one of the pardoned female convicts to sleep in the same bed as a ten-year-old boy with smallpox for six weeks. Of course, nowadays this would raise safeguarding as well as ethical issues. As a result of the experiment, Princess Caroline arranged for orphan children in a local parish to be variolated, and, when these children also came to no harm, two of the royal princesses were treated.

This new procedure was very controversial. A proportion of those treated died as a result. It was argued from church pulpits that the practice was both dangerous and sinful as only God had the power to inflict disease. But, over the century, it became a relatively routine approach to protecting people from smallpox.

There was a belief in the countryside that people who looked after cows and had been infected with cowpox could not catch smallpox (milkmaids were said to have attractive non-pockmarked skin). In 1774, Benjamin Jesty deliberately infected his wife and sons with cowpox in an attempt to protect them from smallpox. What Jenner did was to take this a stage further, to vaccinate his patient with cowpox (the Latin word 'vaccinus' means 'from cows'), and then see if that stopped the symptoms that occurred after a person was variolated with smallpox.

So, in light of this story, was Jenner's experiment on the Phipps lad unethical?

Well, there are certainly things that we might question. Experimenting on the son of his gardener raises concerns about coercion and consent. We might question aspects of the scientific design given that there was only one subject. But to the central charge 'that he deliberately exposed a young child to smallpox solely to see if his vaccination procedure was effective'. I would argue that he is not guilty. What he did do was variolate the child, a standard medical treatment at the time, known to be effective against smallpox. Jenner routinely performed variolation on his patients, and had been variolated himself. He took advantage of this procedure to demonstrate that vaccination really did protect from smallpox - an experiment that changed our world.

Andrew George, Deputy Vice-Chancellor, Brunel University London. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

SOURCED FROM:

http://www.bioedge.org/bioethics/would-jenners-smallpox-experiment-pass-a-research-ethics-committee/11759

and

https://theconversation.com/judging-jenner-was-his-smallpox-experiment-really-unethical-54362

JUST HOW DANGEROUS WAS/IS SMALLPOX?

Smallpox affected all levels of society. In the 18th century in Europe, 400,000 people died annually of smallpox, and one third of the survivors went blind. The symptoms of smallpox, or the “speckled monster” as it was known in 18th-century England, appeared suddenly and the sequelae were devastating. The case-fatality rate varied from 20% to 60% and left most survivors with disfiguring scars. The case-fatality rate in infants was even higher, approaching 80% in London and 98% in Berlin during the late 1800s.

Voltaire, writing of this, estimates that at this time 60% of the population caught smallpox and 20% of the population died of it. Voltaire also states that the Circassians used the inoculation from times immemorial, and the custom may have been borrowed by the Turks from the Circassians

It is reported that somewhere between 2 and 3% of people who were inoculated with smallpox (Variolation) died this was approximately a tenth of that which the actual disease killed.

During the great epidemic of 1721, approximately half of Boston's 12,000 citizens contracted smallpox. The fatality rate for the naturally contracted disease was 14%, whereas Boylston and Mather reported a mortality rate of only 2% among variolated individuals. This may have been the first time that comparative analysis was used to evaluate a medical procedure.

THE MEDICAL CONCLUSION

Jenner's work represented the first scientific attempt to control an infectious disease by the deliberate use of vaccination. Strictly speaking, he did not discover vaccination but was the first person to confer scientific status on the procedure and to pursue its scientific investigation. During the past years, there has been a growing recognition of Benjamin Jesty (1737-1816) as the first to vaccinate against smallpox (21). When smallpox was present in Jesty's locality in 1774, he was determined to protect the life of his family. Jesty used material from udders of cattle that he knew had cowpox and transferred the material with a small lancet to the arms of his wife and two boys. The trio of vaccinees remained free of smallpox, although they were exposed on numerous occasions in later life. Benjamin Jesty was neither the first nor the last to experiment with vaccination. In fact, the use of smallpox and cowpox was widely known among the country physicians in the dairy counties of 18th-century England. However, the recognition of these facts should not diminish our view of Jenner's accomplishments. It was his relentless promotion and devoted research of vaccination that changed the way medicine was practiced.

Late in the 19th century, it was realized that vaccination did not confer lifelong immunity and that subsequent revaccination was necessary. The mortality from smallpox had declined, but the epidemics showed that the disease was still not under control. In the 1950s a number of control measures were implemented, and smallpox was eradicated in many areas in Europe and North America. The process of worldwide eradication of smallpox was set in motion when the World Health Assembly received a report in 1958 of the catastrophic consequences of smallpox in 63 countries (Figure (Figure55). In 1967, a global campaign was begun under the guardianship of the World Health Organization and finally succeeded in the eradication of smallpox in 1977. On May 8, 1980, the World Health Assembly announced that the world was free of smallpox and recommended that all countries cease vaccination: “The world and all its people have won freedom from smallpox, which was the most devastating disease sweeping in epidemic form through many countries since earliest times, leaving death, blindness and disfigurement in its wake”.

Scientific advances during the two centuries since Edward Jenner performed his first vaccination on James Phipps have proved him to be more right than wrong. The germ theory of disease, the discovery and study of viruses, and the understanding of modern immunology tended to support his main conclusions. The discovery and promotion of vaccination enabled the eradication of smallpox: this is Edward Jenner's ultimate vindication and memorial.

SOURCE: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1200696/

Edward Jenner, FRS (17 May 1749 - 26 January 1823), an English physician and scientist who was the pioneer of smallpox vaccination, the world's first vaccine, often called "the father of immunology", and his work is said to have "saved more lives than the work of any other human".

QUOTE: In science credit goes to the man who convinces the world, not the man to whom the idea first occurs. -Francis Galton

OTHER SOURCE USED: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Jenner

In 1797, Jenner sent a short communication to the Royal Society describing his experiment and observations. However, the paper was rejected. Then in 1798, having added a few more cases to his initial experiment, Jenner privately published a small booklet entitled An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae, a disease discovered in some of the western counties of England, particularly Gloucestershire and Known by the Name of Cow Pox. The Latin word for cow is vacca, and cowpox is vaccinia; Jenner decided to call this new procedure vaccination. The 1798 publication had three parts. In the first part Jenner presented his view regarding the origin of cowpox as a disease of horses transmitted to cows. The theory was discredited during Jenner's lifetime. He then presented the hypothesis that infection with cowpox protects against subsequent infection with smallpox. The second part contained the critical observations relevant to testing the hypothesis. The third part was a lengthy discussion, in part polemical, of the findings and a variety of issues related to smallpox. The publication of the Inquiry was met with a mixed reaction in the medical community.

Jenner went to London in search of volunteers for vaccination. However, after 3 months he had found none. In London, vaccination became popular through the activities of others, particularly the surgeon Henry Cline, to whom Jenner had given some of the inoculant. Later in 1799, Drs. George Pearson and William Woodville began to support vaccination among their patients. Jenner conducted a nationwide survey in search of proof of resistance to smallpox or to variolation among persons who had cowpox. The results of this survey confirmed his theory. Despite errors, many controversies, and chicanery, the use of vaccination spread rapidly in England, and by the year 1800, it had also reached most European countries.

Although he received worldwide recognition and many honors, Jenner made no attempt to enrich himself through his discovery. Jenner's continuing work on vaccination prevented him from continuing his ordinary medical practice. He was supported by his colleagues and the King in petitioning Parliament, and was granted £10,000 in 1802 for his work on vaccination. In 1807, after the Royal College of Physicians had confirmed the widespread efficacy of vaccination. the Parliament awarded him £20,000 more. However, he not only received honors but also found himself subjected to attacks and ridicule. Despite all this, he continued his activities on behalf of the vaccination program. Gradually, vaccination replaced variolation, which became prohibited in England in 1840.

In 1803 in London, he became president of the Jennerian Society, concerned with promoting vaccination to eradicate smallpox. The Jennerian ceased operations in 1809. In 1808, with government aid, the National Vaccine Establishment was founded, but Jenner felt dishonoured by the men selected to run it and resigned his directorship. Jenner became a member of the Medical and Chirurgical Society on its founding in 1805 and presented a number of papers there. The society is now the Royal Society of Medicine. He was elected a foreign honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1802. In 1806, Jenner was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Returning to London in 1811, Jenner observed a significant number of cases of smallpox after vaccination. He found that in these cases the severity of the illness was notably diminished by previous vaccination. In 1821, he was appointed physician extraordinary to King George IV, a great national honour, and was also made mayor of Berkeley and justice of the peace. He continued to investigate natural history, and in 1823, the last year of his life, he presented his "Observations on the Migration of Birds" to the Royal Society.

Jenner had married in 1788 and fathered four children. The family lived in the Chantry House, which became the Jenner Museum in 1985. Jenner built a one-room hut in the garden, which he called the “Temple of Vaccinia”, where he vaccinated the poor for free. After a decade of being honored and reviled in more or less equal measure, he gradually withdrew from public life and returned to the practice of country medicine in Berkeley. In 1810, his oldest son, Edward, died of tuberculosis. His sister Mary died the same year and his sister Anne 2 years later. In 1815, his wife, Catherine, died of tuberculosis. Sorrows crowded in on him, and he withdrew even further from public life. In 1820, Jenner had a stroke from which he recovered. On January 23, 1823, he visited his last patient, a dying friend. The next morning Jenner failed to appear for breakfast; later that day he was found in his study. He had had a massive stroke. Edward Jenner died during the early morning hours of Sunday, January 26, 1823. He was laid to rest with his parents, his wife, and his son near the altar of the Berkeley church.

Therefore Edward Jenner is credited with inventing vaccination, but in modern times some have discredited him for deliberately infecting his guinea pig with smallpox to see if he was immune. Many people have considered this to be unethical and un-masonic, but a closer look clears this misconception.

The following article by Andrew George entitled “Would Jenner's smallpox experiment pass a research ethics committee?” answers that very question

WOULD JENNER'S SMALLPOX EXPERIMENT PASS A RESEARCH ETHICS COMMITTEE?

The case seems indisputable. On May 14, 1796 Jenner vaccinated James Phipps, the eight-year-old son of his gardener, with material obtained from a milkmaid who had cowpox. A few weeks later he deliberately infected Phipps with smallpox to see if he would develop the disease. What could be more unethical than exposing a young boy to one of the most deadly diseases in the world simply to see if an unknown procedure would work?

But the story is more complex than this simple narrative suggests. In the 18th century, doctors carried out a procedure known as variolation to protect people from smallpox. This involved exposing people to a small dose of smallpox in order to give them a mild form of the disease, thereby protecting them from the full effects of the disease. It was not a risk-free procedure, and people often died as a result. However, given the terrible mortality of smallpox this was seen to be worthwhile.

Variolation had a long history in China, the Middle East and Africa. Its history in Britain was started by Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, one of the most colourful characters in immunology. She originally eloped with her husband, and then went with him to Constantinople where he was ambassador.

Wortley Montagu wrote extensively about Ottoman life, wore Turkish dress, visited harems and Turkish baths and disguised herself as a man in order to get into the Hagia Sophia mosque. While in Constantinople, she came across the practice of variolation and, in 1718, had her young son Edward variolated on the wrist with a 'blunt and rusty needle'.

Returning to England she resumed life in society. She was a friend of the poet, Alexander Pope, who admired her intelligence and wit and was probably in love with her. In 1721 a smallpox epidemic was threatening Britain, and she persuaded Charles Maitland, her doctor in Constantinople, to variolate her daughter.

Wortley Montagu was a friend of Caroline, the Princess of Wales, who was also worried about the safety of her children. It's thought that this was what prompted the interest of Britain's royal family in variolation.

Sir Hans Sloane (later founder of the British Museum) organised 'The Royal Experiment' in 1721, in which six condemned prisoners from Newgate Prison were variolated. They were then pardoned and released.

You might question several aspects of the ethics of this experiment. To see if this protected them from smallpox, Sloane paid for one of the pardoned female convicts to sleep in the same bed as a ten-year-old boy with smallpox for six weeks. Of course, nowadays this would raise safeguarding as well as ethical issues. As a result of the experiment, Princess Caroline arranged for orphan children in a local parish to be variolated, and, when these children also came to no harm, two of the royal princesses were treated.

This new procedure was very controversial. A proportion of those treated died as a result. It was argued from church pulpits that the practice was both dangerous and sinful as only God had the power to inflict disease. But, over the century, it became a relatively routine approach to protecting people from smallpox.

There was a belief in the countryside that people who looked after cows and had been infected with cowpox could not catch smallpox (milkmaids were said to have attractive non-pockmarked skin). In 1774, Benjamin Jesty deliberately infected his wife and sons with cowpox in an attempt to protect them from smallpox. What Jenner did was to take this a stage further, to vaccinate his patient with cowpox (the Latin word 'vaccinus' means 'from cows'), and then see if that stopped the symptoms that occurred after a person was variolated with smallpox.

So, in light of this story, was Jenner's experiment on the Phipps lad unethical?

Well, there are certainly things that we might question. Experimenting on the son of his gardener raises concerns about coercion and consent. We might question aspects of the scientific design given that there was only one subject. But to the central charge 'that he deliberately exposed a young child to smallpox solely to see if his vaccination procedure was effective'. I would argue that he is not guilty. What he did do was variolate the child, a standard medical treatment at the time, known to be effective against smallpox. Jenner routinely performed variolation on his patients, and had been variolated himself. He took advantage of this procedure to demonstrate that vaccination really did protect from smallpox - an experiment that changed our world.

Andrew George, Deputy Vice-Chancellor, Brunel University London. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

SOURCED FROM:

http://www.bioedge.org/bioethics/would-jenners-smallpox-experiment-pass-a-research-ethics-committee/11759

and

https://theconversation.com/judging-jenner-was-his-smallpox-experiment-really-unethical-54362

JUST HOW DANGEROUS WAS/IS SMALLPOX?

Smallpox affected all levels of society. In the 18th century in Europe, 400,000 people died annually of smallpox, and one third of the survivors went blind. The symptoms of smallpox, or the “speckled monster” as it was known in 18th-century England, appeared suddenly and the sequelae were devastating. The case-fatality rate varied from 20% to 60% and left most survivors with disfiguring scars. The case-fatality rate in infants was even higher, approaching 80% in London and 98% in Berlin during the late 1800s.

Voltaire, writing of this, estimates that at this time 60% of the population caught smallpox and 20% of the population died of it. Voltaire also states that the Circassians used the inoculation from times immemorial, and the custom may have been borrowed by the Turks from the Circassians

It is reported that somewhere between 2 and 3% of people who were inoculated with smallpox (Variolation) died this was approximately a tenth of that which the actual disease killed.

During the great epidemic of 1721, approximately half of Boston's 12,000 citizens contracted smallpox. The fatality rate for the naturally contracted disease was 14%, whereas Boylston and Mather reported a mortality rate of only 2% among variolated individuals. This may have been the first time that comparative analysis was used to evaluate a medical procedure.

THE MEDICAL CONCLUSION

Jenner's work represented the first scientific attempt to control an infectious disease by the deliberate use of vaccination. Strictly speaking, he did not discover vaccination but was the first person to confer scientific status on the procedure and to pursue its scientific investigation. During the past years, there has been a growing recognition of Benjamin Jesty (1737-1816) as the first to vaccinate against smallpox (21). When smallpox was present in Jesty's locality in 1774, he was determined to protect the life of his family. Jesty used material from udders of cattle that he knew had cowpox and transferred the material with a small lancet to the arms of his wife and two boys. The trio of vaccinees remained free of smallpox, although they were exposed on numerous occasions in later life. Benjamin Jesty was neither the first nor the last to experiment with vaccination. In fact, the use of smallpox and cowpox was widely known among the country physicians in the dairy counties of 18th-century England. However, the recognition of these facts should not diminish our view of Jenner's accomplishments. It was his relentless promotion and devoted research of vaccination that changed the way medicine was practiced.

Late in the 19th century, it was realized that vaccination did not confer lifelong immunity and that subsequent revaccination was necessary. The mortality from smallpox had declined, but the epidemics showed that the disease was still not under control. In the 1950s a number of control measures were implemented, and smallpox was eradicated in many areas in Europe and North America. The process of worldwide eradication of smallpox was set in motion when the World Health Assembly received a report in 1958 of the catastrophic consequences of smallpox in 63 countries (Figure (Figure55). In 1967, a global campaign was begun under the guardianship of the World Health Organization and finally succeeded in the eradication of smallpox in 1977. On May 8, 1980, the World Health Assembly announced that the world was free of smallpox and recommended that all countries cease vaccination: “The world and all its people have won freedom from smallpox, which was the most devastating disease sweeping in epidemic form through many countries since earliest times, leaving death, blindness and disfigurement in its wake”.

Scientific advances during the two centuries since Edward Jenner performed his first vaccination on James Phipps have proved him to be more right than wrong. The germ theory of disease, the discovery and study of viruses, and the understanding of modern immunology tended to support his main conclusions. The discovery and promotion of vaccination enabled the eradication of smallpox: this is Edward Jenner's ultimate vindication and memorial.

SOURCE: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1200696/

Edward Jenner, FRS (17 May 1749 - 26 January 1823), an English physician and scientist who was the pioneer of smallpox vaccination, the world's first vaccine, often called "the father of immunology", and his work is said to have "saved more lives than the work of any other human".

QUOTE: In science credit goes to the man who convinces the world, not the man to whom the idea first occurs. -Francis Galton

OTHER SOURCE USED: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Jenner